Cognitive warfare and the Nordic threat landscape

Author: Dr. Benjamin J. Knox, researcher with Norwegian Armed Forces Cyber Defence and associate professor at Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU).

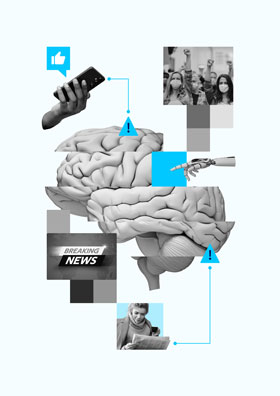

In today’s hyper-connected digital society, the boundaries between physical and psychological conflict have blurred. Warfare is no longer limited to physical force or even cyberattacks. A more insidious form of conflict, cognitive warfare, is now emerging as a critical national security threat. Unlike traditional forms of warfare defined by control of physical territory, cognitive warfare is not trapped in this 20th-century perspective. It targets the cognition itself. At its core, cognitive warfare is a threat that alters perceptions, disrupts trust boundaries, erodes decision-making and turns a target’s own cognitive processes against them.

Rather than focusing on influencing what a target believes, modern cognitive operations increasingly target how a target thinks. It does this by reshaping the mental machinery that produces ideas, decisions and perceptions. Examples include Cambridge Analytica tailoring the style of information delivery in the 2016 U.S election; Russian “Reflexive Control” operations to seed contradictory, ambiguous narratives to overload cognitive processing, fostering paralysis and distrust in decision-making; anti-vaccination misinformation ecosystems that target emotion by encouraging anecdotal thinking over statistical reasoning; and ISIS online radicalisation and recruitment pipelines that altered the criteria for evaluating truth and authority. Nordic societies, with their high levels of digital penetration and use of online platforms for public debate, are especially exposed to such techniques.

Cognitive warfare aims to manipulate input-output relationships in neural systems. These systems include human brains, artificial intelligence, social networks, and cyber-physical systems (such as industrial robots, self-driving cars, smart home technology, and military platforms). For military, government, civilian, and commercial sectors, this evolving threat vector introduces a complex and largely uncharted risk landscape that challenges the integrity of networks, the resilience of people, and ultimately national security.

Cognitive Superiority for NATO is defined as an ability to excel in understanding and decision-making that enables out-thinking and out-manoeuvring the adversary. In other words, it is about possessing faster, deeper, and broader understanding of the operating environment, your adversary and yourself, and about applying better, more effective decision-making than adversaries apply. It is also adversary centric – the NATO Military Instrument of Power must be able to out-think the enemy to be able to gain and maintain the advantage when shaping and contesting below the threshold of armed conflict, and when fighting a conflict.

‘Grey zone’ activities refer to hostile activities below the threshold of direct, state-on-state conflict, designed to coerce governments or simply erode national power and the ability to function in areas of diplomatic, informational, military and economic interest. Conflated with this is Hybrid Warfare, understood as a level of hostile intent that escalates from influencing and interfering operations, to conflict. Often hybrid activities result from Grey zone activities failing to achieve the goals of a state. Hybrid actions are those conducted by state or non-state actors that combine overt and covert military and non-military means to undermine or harm a target. This includes activities that exploit the thresholds of detection and attribution, blurring the lines between war and peace.

The conflict continuum

As a society we must accept that conflict occurs on a continuum where there is neither war nor peace. This new distinction has implications for how we understand and relate to “war”. Of equal concern is how we chose to perceive “crisis”, when cognitive warfare is the crises we can’t [or don’t want to] see. This new context has revealed itself as a persistent situation with four types of rivalry: competition, confrontation, coercion, and armed conflict.

Conflict continuum:

Competition is normally between states. Here we can see trade wars, pressure, collection of intelligence on the opponent, theft of research results and industrial secrets, cyber espionage, monitoring and mapping.

Confrontation is direct opposition between actors, not just competition. Confrontation can take the form of expulsion of diplomats, recruitment of spies, influencing the press and individuals, attempts to change the population's perspective, sow doubt and create disagreement, more extensive cyberattacks, and pressure on countries.

Coercion is targeted pressure to make the opponent change its behavior through threats of force or actual use of limited force, also referred to as coercive diplomacy. Political manipulation, psychological warfare, ultimatums with threats of military attacks, blockades, proxy attacks, sabotage, occupation of parts of territories, major cyberattacks and cyber sabotage that cripple infrastructure, manipulation of media and front organizations that create internal violent conflict and terrorist attacks.

Armed Conflict is warfare in one form or another. Here we are in the traditional image of the use of military force — that is, transitioning from a state of peace to war through invasion and deployment of military forces in operations. However, the transition may be ambiguous, using tools also familiar from confrontation and coercion.

Why we must act now

Russia considers itself to be in strategic conflict with the West over values and interference in what it regards as its legitimate sphere of interest. Beijing’s approach to power is rooted in the Chinese national strategy, which aims to achieve the "great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation" by 2049. Whether the former, with its long-standing doctrinal application of “information confrontation” codified in “New Generation Warfare” (Война нового Поколения), or the latter shifting toward “intelligentized” warfare (a military doctrine focused on cognitive operations to “capture the mind” of one’s foes), we face threats that continue to represent a fundamental paradigm shift in modern conflict. Recent U.S. activity in Greenland, reportedly employing cognitive means within broader grey zone tactics, further underscores that such practices are not confined to adversaries alone but are becoming characteristic of contemporary great-power competition.

The military instrument

NATO frames the threat of cognitive warfare as a contest for cognitive superiority. Achieving and maintaining cognitive superiority is acknowledged as a persistent, unconventional challenge that extends beyond the military instrument. It demands deliberate, synchronized military and non-military activities to gain, maintain, and protect cognitive advantage. While the application of military power is effective, the conduct of defensive and offensive cognitive warfare activities is often poorly defined. They lack the necessary policy, planning, and capabilities that support deterrence below the Article 5 threshold. Just as cyberspace is now recognized as too vast, dynamic, and critical to be constrained within a single military service; the framing of cognitive warfare must not be limited by artificially restricting thinking across the conflict continuum. Addressing this challenge requires adaptation and transformation within and beyond the traditional mandates and boundaries of the military instrument to safeguard national sovereignty in modern warfare.

The telecommunications provider

Telecommunications play a central role in digital life, and cognitive operations are supercharged by cyberspace and the virtual dimension. As a critical national infrastructure provider, Telenor is a useful example as it connects individuals, institutions, and state services. This same connectivity creates multiple access points for adversaries to conduct multiple types of operations in the cognitive dimension. These technological vectors are used to interfere without physical confrontation meaning cognitive warfare is deeply digital in method. Cognitive operations exploit data, thriving on the infrastructure and opportunities created by digital platforms, communication networks, and online behaviours. In other words, the internet and cyber systems of today provide the ultimate operational terrain of cognitive conflict.

Beyond boundaries: Appreciating the action space & the UnCODE framework

The key to understanding cognitive warfare is to fully grasp the expanded action space it occupies, as well as the long-term strategic goals of its application. Recognising cognitive warfare as an action space elevates it beyond merely an academic exercise, instead it reveals how it expands, evolves and accelerates with developments in science and technology, across interconnected domains (in particular: cyber, social, biological, technological). Recent work developing the UnCODE framework captures this, making clear the full range of goals available to adversaries, and classifies these into five categories:

Unplug: eliminating a neural system’s ability to process or transmit information.

Corrupt: degrading a system’s cognitive capacity or infrastructure.

disOrganise: biasing how information is processed, leading to incoherent or manipulated outputs.

Diagnose: monitoring and analysing cognitive systems to inform future attacks.

Enhance: improving one’s own cognitive systems to gain strategic advantage.

These inter-related yet qualitatively distinct cognitive warfare goals reveal how information processing, whether in neurons, networks, or algorithms, is the key terrain of cognitive conflict. How an actor or agentic capability gains access can be direct or indirect, depending on whether the methods chosen are directly or indirectly interfering with the targeted neural system where cognition occurs. Thus, cognitive effects can either be incurred via direct manipulation of neurocognitive processes and their effects on behaviour; or indirectly affecting ecologies/environments, and socio-economics to ultimately reach the target and affect a behavioural output of cognition.

The security policy situation combined with technological developments, and the fact that cyber now surrounds us (best described as the Internet of Everything (IoE), i.e., not only made up “of things”, but also of data, processes and people) means that how defensive cyber operations fit into individual and societal level cognitive security is evolving.

No time to waste

At a time when novel methods and capabilities are emerging from advances in the study of human cognition and neuroscience, combine with the rapid evolution of Emerging Disruptive Technologies (EDTs), the Nordic region has set bold ambitions for digital transformation. Norway has set its ambition to become the world’s most digitized nation by 2030, while its neighbours in Denmark, Sweden and Finland are pursuing similarly ambitious national strategies. Together, these efforts reflect a wider Nordic commitment to digitalisation as a driver of competitiveness, welfare, and security.

Yet, as the boundaries between the virtual, cognitive, and physical dimensions grow increasingly indistinct, the opportunities for adversaries to exploit the conflict continuum are also multiplying. Digitalisation brings efficiency and growth. It also amplifies the exposure of cognitive assets1 to threats that target trusted boundaries by interfering and attempting to destabilise democratic societies. In this context, the Nordic strategies sit alongside the European Union’s Digital Decade and the Nordic-Baltic Roadmap for Digitalisation 2025–2030. These frameworks emphasise secure and sustainable digital infrastructures, interoperable public services, trusted cross-border data flows, and digital skills as essential to building resilience. They are not only growth strategies, but also instruments of protection and security, designed to harden societies against adversarial opportunities in the cognitive warfare action space.

Among these, cognitive and media-related skills are particularly vital. A key element of such skills and of resilience more broadly lies not only in technical competence but also in education and societal preparedness. Finland, for example is embedding media literacy into its national curriculum, training students from an early age to recognise manipulation and evaluate information critically. This long-term investment in “cognitive security” strengthens democratic culture, individual, organisational and societal resilience, complementing more traditional security and defence measures. Other Nordic countries are exploring similar approaches, recognising that the strength of digital societies rests not only on secure infrastructures but also on informed and discerning citizens.

For Norway, the regional framing is crucial. Its national digitalisation strategy (2024-2030) explicitly acknowledges the risks to democracy and national security that accompany this transformation. Policy frameworks such as act. Meld. St. 33 (2024-2025), which directs the Armed Forces to contribute to the further development of resistance to cognitive warfare and the Totalberedskapsmeldingen (Meld. St. 9, 2024-2025) that points in a whole new direction for developing a civil society that supports military efforts and resists complex threats, both point a way forward. Seen in a Nordic and European context, these measures underline that safeguarding cognitive security is not a national undertaking alone, but a collective regional responsibility.

Recommendation and tasks

The threat landscape is being shaped by actors who have a clear idea of how to achieve their cognitive warfare goals. As such, we can no longer treat cognitive warfare as a peripheral concern. Individual and collective efforts are necessary, and the Defence will lead where it can.

To meet this challenge, we must assemble an interdisciplinary team of experts from the Defence, public sector, and business . Their mission must be to reimagine how we want to defend cyberspace to deter and contest in the cognitive warfare action space. The actionable steps required are:

Work together, across sectors, borders and industries to leverage knowledge, data and information to empower timely cognitive superiority.

Shift the approach to cyber defence from system-centric that prioritizes the needs and capabilities of a technical system, to a cognition-aware model.

Reappraise mandates. Cyber leaders need to be empowered and encouraged to review their role and responsibility considering the expanded cyber domain and cognitive warfare action space.

Develop tactics to protect our cognitive assets*, based upon UnCODE goals in action spaces with fewer rules and regulations.

* A “Cognitive Asset” is any process, state, anatomical or organizational structure, tool or technology that is related to a human or non-human cognitive system. Any loss of integrity or protection of this asset is- or has the potential to produce an undesirable outcome.

The unifying purpose is to give the Nordic region a competitive advantage in the terra incognita of cognitive warfare from a cyber defence perspective.

Sources used in this chapter:

Nasjonal sikkerhetsstrategi (2025).

Johnson, R., (2021). Hybrid warfare and counter-coercion. In The Conduct of War in the 21st Century (pp. 45-57). Routledge.

Ask, T. F., Lugo, R. G., Sütterlin, S., Canham, M., Hermansen, D., & Knox, B. (2024a). The UnCODE System: A Neurocentric Systems Approach for Classifying the Goals and Methods of Cognitive Warfare. The HFM-361 Symposium on Mitigating and Responding to Cognitive Warfare, P12 (Madrid, Spain). DOI: 10.14339/STO-MP-HFM-361-P12-PDF.

Annett, E & Giordano, J., (2025), The “Ins” and “Outs” of Cognitive Warfare: What’s the Next Move? INSS Strategic Insights, National Defence University.

The European Centre for Countering Hybrid Threats (Hybrid CoE).

Meld. St. 33 (2024-2025), Status, fremdrift, utfordringer og risiko i gjennomføring av langtidsplanen for forsvarssektoren 2025–2036.

Meld. St. 9 (2024-2025), Totalberedskapsmeldingen Forberedt på kriser og krig.

Fremtidens digitale Norge. Nasjonal digitaliseringsstrategi 2024-2030.